- It can cost $750 and take months for trans people to legally change their names and gender markers.

- Some states prohibit legal gender changes or require proof of costly transition surgery.

- In Maryland, a group helps trans people pay fees and jump through hoops, but many trans people still struggle.

- This article is part of a series called "The Cost of Inequity," examining the hurdles that marginalized and disenfranchised groups face across a range of sectors.

Darcy Corbitt, a graduate student in developmental psychology at Auburn University, hoped things would go smoothly when she swapped her North Dakota driver's license for an Alabama one. They didn't.

Corbitt, who is transgender, said the license clerk's courtesy faded as soon as she came across Corbitt's licensing records from having previously lived in Alabama. It listed her gender as male, and the clerk refused to change it. She began loudly discussing the issue with other employees, at one point referring to Corbitt as "it."

"She said, 'Well, you have to have surgery.' And I said, 'Well, how do you know I haven't had surgery?'" Corbitt recalled. "It's none of their business, No. 1, and, No. 2, it's stupid. What I have or don't have between my legs, it doesn't impair or enhance my ability to drive."

Not long after, Corbitt and her lawyers with the ACLU sued the state of Alabama. A federal judge found the policy unconstitutional and Corbitt got a license that lists her gender as female.

She still had to pay for it. "That was the most insulting bit," she said.

Alabama isn't the only state in which trans people can struggle to change their names and gender markers on legal documents. When Corbitt and her co-plaintiffs filed a lawsuit, the ACLU said nine states required proof of gender-reassignment surgery before they'd change a driver's listed gender. As of last year, that was still the case, according to the website of the National Center for Transgender Equality, or NCTE.

More than a marker

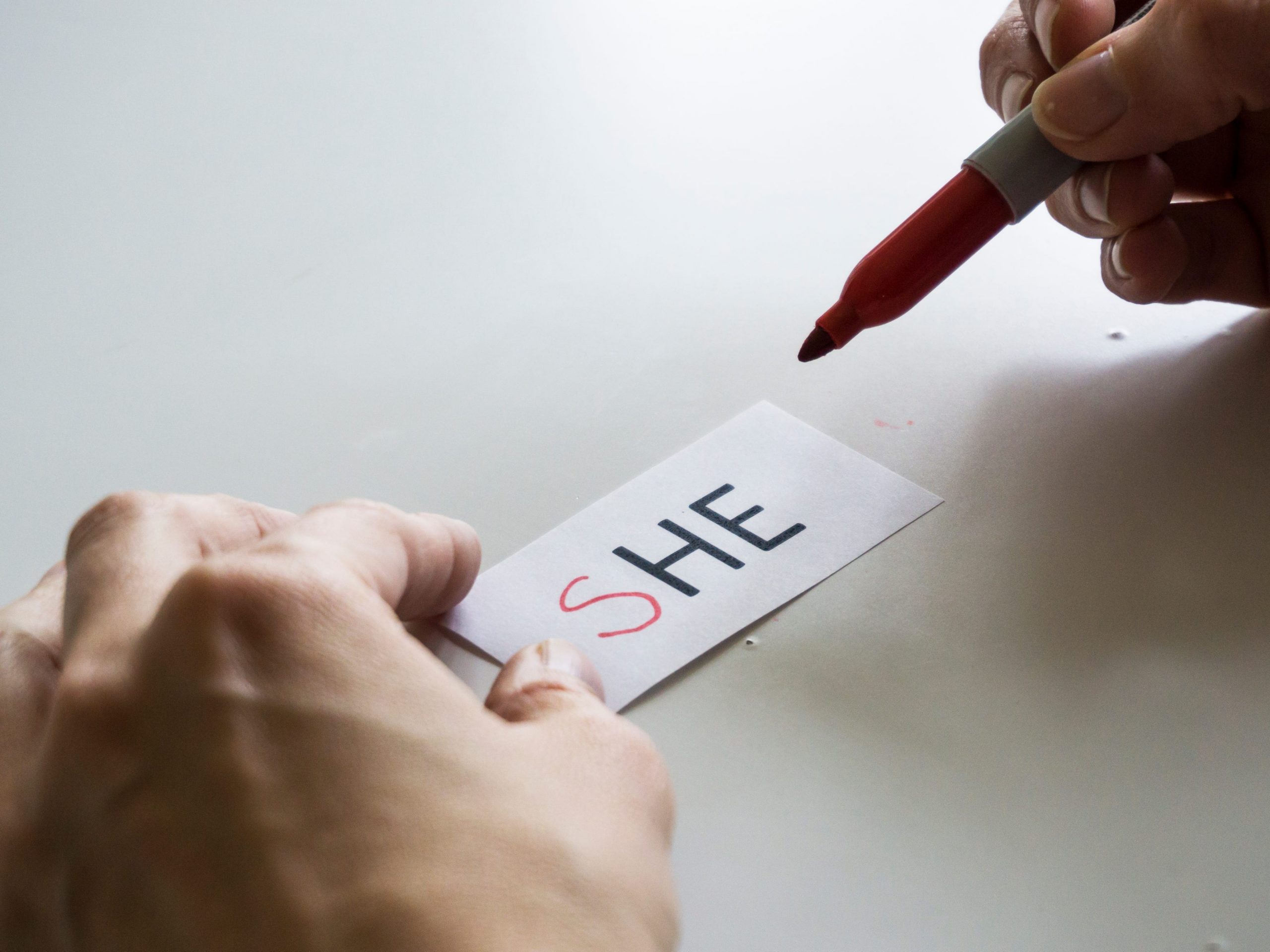

People who identify with the gender they were assigned at birth rarely have to think about how people will react to their official documents. But according to the 2015 US Trans Survey, more than two-thirds of trans people didn't have a single piece of identification with their preferred name and gender marker. (An updated survey is set to be released later this year, according to a spokesperson for the NCTE, which conducts the survey.)

Presenting an ID that doesn't match your outward appearance can be awkward, but sometimes it's worse than that. A quarter of trans people said they were verbally harassed after showing an ID that didn't correspond with their gender presentation, according to the survey. Smaller shares of respondents said they were denied service or even assaulted.

A name change is relatively easy, though it's not fast or cheap. It often requires paying court fees, document-copying fees, and sometimes the cost of putting a public notice in a newspaper. Most respondents to the 2015 survey who changed their names paid between $100 and $500. Sometimes the process can be done entirely on paper, but some courts require people to appear in person.

Some groups can offer advice or financial help for name changes. Trans Maryland has helped over 300 people navigate the process of changing their legal names and updating their Social Security cards or driver's licenses to match their names or gender markers, according to Lee Blinder, the group's executive director. The costs can run to $700 or higher, depending on how many documents a person seeks to update and whether they change their legal name, gender or both.

The costs vary widely. In California, filing a name-change action costs $435 and comes with a six-week wait. In New York, the process takes a day in court and costs $65, plus $35 for an ad in the Irish Echo, the cheapest newspaper for public notices, plus $6 per copy of a court order, according to the Sylvia Rivera Law Project.

Even small fees could be a deterrent to people with low incomes. About 38% of trans people had household incomes below $25,000 in 2014, and 35% of those who haven't gotten a legal name change said they did so for cost reasons, according to the 2015 survey.

Gender-marker changes are harder

It is a lot harder for trans people to change their gender markers. For all document types asked about on the US Trans Survey - driver's licenses, Social Security records, passports, school records, and birth certificates - fewer trans people had updated their gender than their name.

In some states, updating a birth certificate or driver's license is as simple as attesting that a person's gender identity has changed. But more states and the federal government require that a healthcare provider or other professional certify that someone has received "appropriate clinical treatment" before changing their gender marker.

The lack of a gender-neutral marker - like "X" - in most states and at the federal level can also cause difficulties with doctors and medical insurers, according to Blinder. Blinder, who uses the pronouns "they" and "them," said Social Security numbers are often tied to insurance and healthcare options.

"That means every time you go to the doctor's, you have to misrepresent yourself," they said.

Nine states require genital surgery to change a driver's license, and even more require such surgery for a birth certificate, according to NCTE tallies from 2020. Insurers often require six months to a year of hormone therapy and sign-offs by mental-health professionals beforehand. Surgeons' waitlists add at least another six months to the process, according to Carl Streed, a primary-care doctor in Boston who provides gender-affirming healthcare.

"We're talking about needing multidisciplinary care to access surgical care," he said. "I wish it were a lot faster."

At least three states besides Alabama - Tennessee, Ohio, and New York - face lawsuits over gender markers on driver's licenses or birth certificates, and the stakes for trans people are high. For several months, Corbitt said she couldn't drive because her license expired while the case was pending. Alabama has issued her a license with an "F" gender marker, but it has also appealed the court's decision.

"If we lose the appeal, heaven forbid, I won't drive," Corbitt said. "I believe that God has made me the way that I am."